Actions (including sending NEAR)

We're going to introduce a new Action: Transfer. In this chapter, we'd like the first person to solve the crossword puzzle to earn some prize money, sent in NEAR.

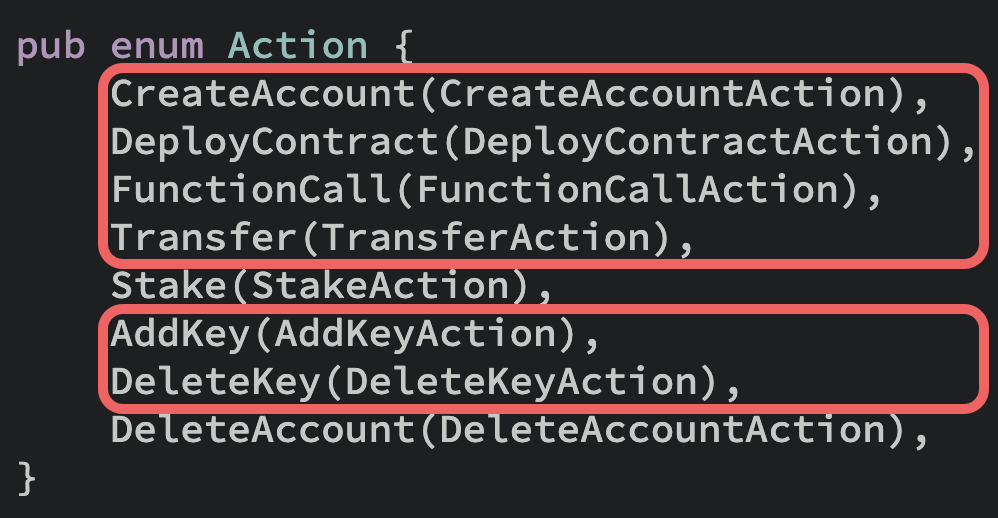

We've already used Actions in the previous chapter, when we deployed and initialized the contract, which used the DeployContract and FunctionCall Action, respectively.

The full list of Actions are available at the NEAR specification site.

By the end of this entire tutorial we'll have used all the Actions highlighted below:

Actions from within a contract

When we deployed and initialized the contract, we used NEAR CLI in our Terminal or Command Prompt app. At a high level, this might feel like we're lobbing a transaction into the blockchain, instructing it to do a couple actions.

It's important to note that you can also execute Actions inside a smart contract, which is what we'll be doing. In the sidebar on the left, you'll see a section called Promises, which provides examples of this. Perhaps it's worth mentioning that for the Rust SDK, Promises and Actions are somewhat synonymous.

A contract cannot use the AddKey Action on another account, including the account that just called it. It can only add a key to itself, if that makes sense.

The same idea applies for the other actions as well. You cannot deploy a contract to someone else's account, or delete a different account. (Thankfully 😅)

Similarly, when we use the Transfer Action to send the crossword puzzle winner their prize, the amount is being subtracted from the account balance of the account where the crossword contract is deployed.

The only interesting wrinkle (and what may seem like an exception) is when a subaccount is created using the CreateAccount Action. During that transaction, you may use Batch Actions to do several things like deploy a contract, transfer NEAR, add a key, call a function, etc. This is common in smart contracts that use a factory pattern, and we'll get to this in future chapters of this tutorial.

Define the prize amount

Let's make it simple and hardcode the prize amount. This is how much NEAR will be given to the first person who solves the crossword puzzle, and will apply to all the crossword puzzles we add. We'll make this amount adjustable in future chapters.

At the top of the lib.rs file we'll add this constant:

Loading...

As the code comment mentions, this is 5 NEAR, but look at all those zeroes in the code!

That's the value in yoctoNEAR. This concept is similar to other blockchains. Bitcoin's smallest unit is a satoshi and Ethereum's is a wei.

Adding Transfer

In the last chapter we had a simple function called guess_solution that returned true if the solution was correct, and false otherwise. We'll be replacing that function with submit_solution as shown below:

Loading...

Note the last line in this function, which sends NEAR to the predecessor.

The last line of the function above ends with a semicolon. If the semicolon were removed, that would tell Rust that we'd like to return this Promise object.

It would be perfectly fine to write the function like this:

pub fn submit_solution(&mut self, solution: String, memo: String) -> Promise {

// …

// Transfer the prize money to the winner

Promise::new(env::predecessor_account_id()).transfer(PRIZE_AMOUNT)

}

Predecessor, signer, and current account

When writing a smart contract you'll commonly want to use env and the details it provides. We used this in the last chapter for:

- logging (ex:

env::log_str("hello friend")) - hashing using sha256 (ex:

env::sha256(solution.as_bytes()))

There are more functions detailed in the SDK reference docs.

Let's cover three commonly-used functions regarding accounts: predecessor, signer, and current account.

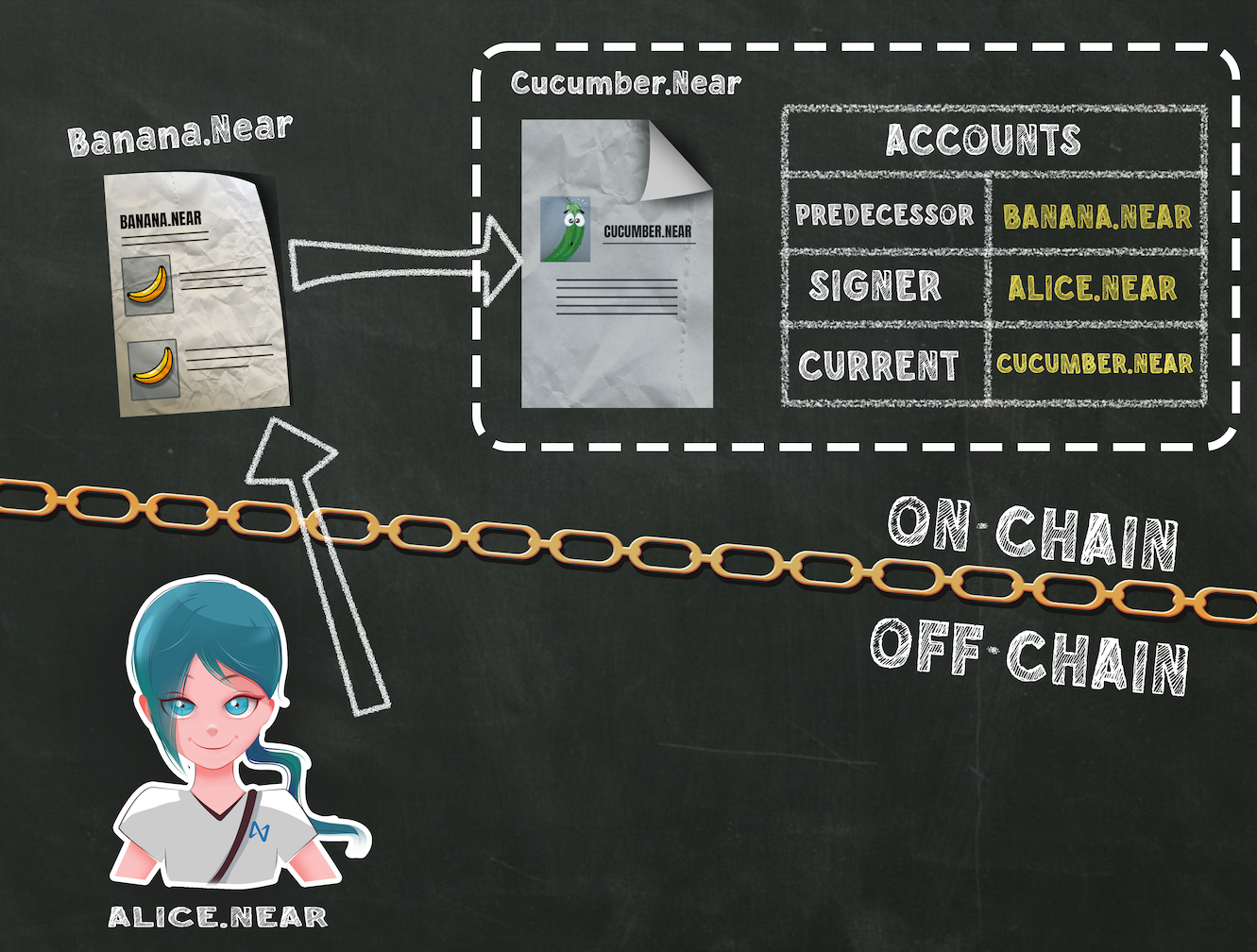

From the perspective of a contract on cucumber.near, we see a list of the predecessor, signer, and current account.

Art by yasuoarts.near

-

predecessor account —

env::predecessor_account_id()This is the account that was the immediate caller to the smart contract. If this is a simple transaction (no cross-contract calls) from alice.near to banana.near, the smart contract at banana.near considers Alice the predecessor. In this case, Alice would also be the signer.

When in doubt, use predecessorAs we explore the differences between predecessor and signer, know that it's a more common best practice to choose the predecessor.

Using the predecessor guards against a potentially malicious contract trying to "fool" another contract that only checks the signer.

-

signer account —

env::signer_account_id()The signer is the account that originally signed the transaction that began the blockchain activity, which may or may not include cross-contract calls. If a function calls results in several cross-contract calls, think of the signer as the account that pushed over the first domino in that chain reaction.

Beware of middlemenIf your smart contract is checking the ownership over some assets (fungible token, NFTs, etc.) it's probably a bad idea to use the signer account.

A confused or malicious contract might act as a middleman and cause unexpected behavior. If alice.near accidentally calls evil.near, the contract at that account might do a cross-contract call to vulnerable-nft.near, instructing it to transfer an NFT.

If vulnerable-nft.near only checks the signer account to determine ownership of the NFT, it might unwittingly give away Alice's property. Checking the predecessor account eliminates this problem.

-

current account —

env::current_account_id()The current account is "me" from the perspective of a smart contract.

Why would I use that?There might be various reasons to use the current account, but a common use case is checking ownership or handling callbacks to cross-contract calls.

Many smart contracts will want to implement some sort of permission system. A common, rudimentary permission allows certain functions to only be called by the contract owner, AKA the person who owns a private key to the account for this contract.

The contract can check that the predecessor and current account are the same, and trust offer more permissions like changing contract settings, upgrading the contract, or other privileged modifications.